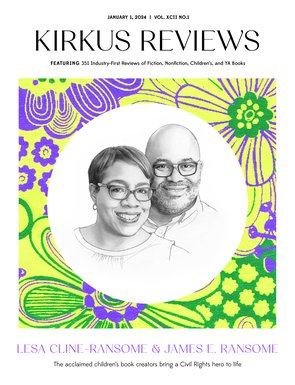

Over the past two decades, author Lesa Cline-Ransome and illustrator James E. Ransome have set the gold standard for picture-book biographies. The husband-and-wife team have collaborated on acclaimed works about Harriet Tubman, Venus and Serena Williams, Alvin Ailey, and Satchel Paige. Their latest, Fighting With Love: The Legacy of John Lewis (Paula Wiseman/Simon & Schuster, Jan. 9), focuses on key moments in the life of the Civil Rights leader-turned-congressman: the sit-ins he took part in, his travels through the South with Freedom Riders in the summer of 1961, and the March on Washington, where he spoke alongside luminaries such as Martin Luther King Jr. Though it’s only January, this potent work is already one of the most relevant books of 2024, certain to inspire the next generation of activists to fight for what they believe in.

The book was a natural next step for the pair, who’ve long idolized Lewis. “I’ve been admiring him through history books and watching him in the halls of Congress for years and years,” Cline-Ransome tells Kirkus via Zoom from the couple’s home in Rhinebeck, New York. “One of the things that’s most impressed me about John Lewis is both his passion for politics and for justice, equality, and civil rights, but also the ways that [all] intersects with his faith and immense love of humanity. He’s a fighter, but he’s also incredibly honest and believes and trusts in our humanity.”

The book was a natural next step for the pair, who’ve long idolized Lewis. “I’ve been admiring him through history books and watching him in the halls of Congress for years and years,” Cline-Ransome tells Kirkus via Zoom from the couple’s home in Rhinebeck, New York. “One of the things that’s most impressed me about John Lewis is both his passion for politics and for justice, equality, and civil rights, but also the ways that [all] intersects with his faith and immense love of humanity. He’s a fighter, but he’s also incredibly honest and believes and trusts in our humanity.”

Ransome, too, has always looked up to Lewis, in large part because of his courage, exemplified by his actions on Bloody Sunday in 1965, when he led marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. “I was just a baby [at the time],” he says. “Lesa wasn’t even born yet. Seeing that footage of him—standing there and knowing that in the next few minutes, there’s going to be pain. He’s going to be beaten, and beaten hard. To cross that bridge and to walk into that—it’s always moved me.”

He’s long felt a kinship with Lewis, too. James’ family were sharecroppers, like Lewis’, and Lewis reminded him of his uncles. “I felt very connected to him from the beginning,” he says. In 2017, Lesa and James met Lewis briefly at the 10th National Conference of African American Librarians in Atlanta—a moving experience for both. “I’m pretty sure I started crying,” says Lesa. “He was so comfortable among his constituents. You could see wherever he went, he was treated like family.”

Creating this work was daunting, especially for Lesa, who finds that the more she admires someone, the tougher it is to write about them. “I felt that way with our book Before She Was Harriet. I was very concerned about my ability to capture this incredible woman in a 32-page picture book.” When James proposed writing about Lewis, Lesa was initially hesitant, but editor Paula Wiseman encouraged her to try. “It took me a very, very long time to figure out how to tell the story,” she says. “I had to go through a lot of different versions in order to find the right one.”

Lesa started by reading biographies of Lewis, including Jon Meacham’s His Truth Is Marching On (2020). “One of the things that really stood out was his immense faith and his belief that no child is born in hate.” She initially structured the book as a more linear biography, but that approach didn’t capture his essence. “I felt that I wasn’t really a believer in this principle of nonviolent protest; I still wasn’t fully understanding it.”

That changed in November 2020. The week before the presidential election, caravans of Trump supporters descended on Rhinebeck, honking horns and yelling. She and other protesters stood outside with signs, making it clear hate wasn’t welcome in their community. As one of the few people of color in her predominantly white town, Lesa was immediately targeted by the MAGA crowd, who yelled racial epithets at her. “Lesa before researching John Lewis might have responded differently,” she says. “But I started thinking about how John Lewis might have responded in this moment. When he attended these protests, he would always try to envision the people who were spitting at him and beating him as babies, [to imagine] who they were before they became ingrained with hate. And that’s what I did.”

Thinking of Lewis helped get her through the experience. “I realized that this is what nonviolent protest is—that you can experience a certain calm and an understanding of the people who are opposing you.” His example also radically transformed the book. “I remember coming home, going to my desk and sitting down, and because I understood what nonviolent protest was about, I better understood John Lewis. He was protesting, but he was doing it with love. And that changed the direction of the story.”

James found himself shifting gears, too. The book ends just before Lewis crosses the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and James initially wanted to conclude with wordless depictions of the protesters being attacked by police. Remembering a promise he’d made to himself years ago “not to show someone being hit or beaten,” he instead closed with an illustration of Lewis praying. Lesa knows that he made the right choice: “It’s a beautiful final spread because it shows who [Lewis] is: He’s a man of faith.”

James opted to use collage rather than paint, as he’s done with previous works on the Civil Rights Movement. “I didn’t want to paint the same sort of pictures. I tried to challenge myself.” On one spread, he glued newsprint to the page to depict the chicken coop on the Alabama farm where Lewis grew up. On another, he used images of maps to show how far Lewis and the other Freedom Riders traveled. “Those types of visual challenges are what I look forward to when I’m doing a book these days, so I’m excited when that hard work pays off.”

Collaborating with a spouse on a book brings many benefits. As Lesa notes, “The best part about being a married working couple is that we get to do our research together.” While she was preparing to write her YA novel, For Lamb (2023), the two visited several Civil Rights–related sites in Montgomery, Alabama, and stopped at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, all of which informed Fighting With Love. “It’s one thing to read great books, but there’s really nothing like visiting an area, talking to people, walking in the footsteps of the people that you are writing about,” Lesa says.

Both Lesa and James hope that readers will attempt to walk in Lewis’ footsteps. James advises young people to choose love, as Lewis did. “Life’s just way too short to carry around this boulder of hate around with you,” he says. Lesa wants readers “to keep marching forward and continuing the work that John Lewis left us.” She acknowledges how hard that is, especially now. “But I think that on the journey to embracing a philosophy of love, we could certainly embrace a philosophy of listening and understanding.…I think listening is the first step in the journey toward love.”

Mahnaz Dar is a young readers’ editor.